How VCs can avoid another bloodbath as the clean-tech boom 2.0 begins

Last decade’s clean-tech gold rush ended in disaster, wiping out billions in investments and scaring venture capitalists away for years.

But a new investment boom is building again, this time around a broader set of climate-related technologies. Funding has soared more than 3,750% since 2013, according to a PwC report this fall, as numerous climate-focused venture firms emerge and established players return to the field (including some that got scorched the last time). Investments are poised to rise further as market, policy, and technological forces align to make venture capitalists and entrepreneurs more confident.

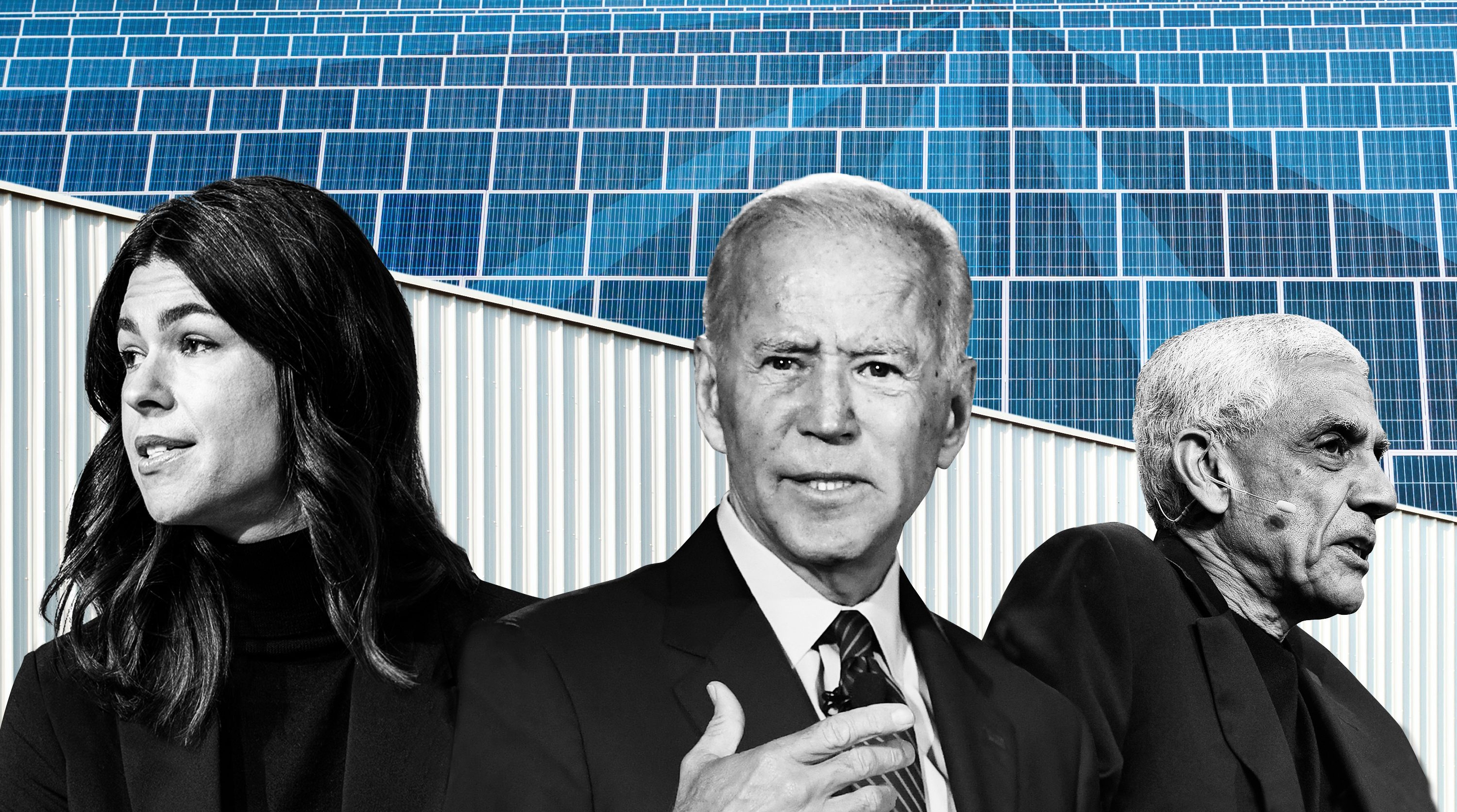

One of these factors is President-elect Joe Biden’s pledge to push through climate-friendly legislation, regulations, and executive orders. There are also rising hopes that Congress will pass stimulus bills that would funnel massive amounts of money into clean tech, much as the Obama administration did during the global financial crisis.

Regardless of what happens on the US federal level, growing numbers of states, nations, and corporations are committing to achieve net zero emissions in the coming decades. Those targets alone promise to create significant demand for clean energy and other climate-related technologies.

“Climate has many, many problems, with many different solutions—and that will create many opportunities to build big, valuable companies,” Andrew Beebe, managing director of Obvious Ventures, which invests in clean-energy and transportation startups, said in an email. “From batteries to mobility to energy efficiency to carbon capture and beyond.”

The ultimate size and fate of the next boom, however, could depend on how quickly and fully the economy recovers from the devastating covid-driven downturn—and how well investors learned their lessons from the last bust.

What went wrong

The original clean-tech boom was a bloodbath. Investors plowed some $25 billion into startups from 2006 to 2011—but they lost more than half their money in the end, according to an MIT Energy Initiative analysis in 2016. In fact, more than 90% of the companies funded after 2007 didn’t even return the capital invested.

A variety of factors were to blame.

The global recession dried up the market for new or follow-on investments. The collapse of silicon prices as China scaled up solar panel production hammered thin-film startups and others pursuing alternative approaches. And the advanced biofuel sector struggled to compete as the downturn undercut oil prices and the rise of fracking tapped into new domestic natural-gas reserves.

But the MIT analysis concluded that “external economic trends” weren’t the primary problem. The bigger issue was that startups still deep in the research-and-development stage were a poor fit with the venture capital industry, which was counting on the sorts of high returns in three to five years that it enjoyed in software.

Clean-tech companies required too much money and time to demonstrate and scale up their technologies, says John Weyant, a professor of management science and engineering at Stanford, who coauthored a book examining what went wrong.

Advanced biofuels, thin-film solar companies, and all sorts of energy storage startups of the era were simply too immature and too expensive to be commercialized—and in many cases they remain so today. Weyant’s book also concludes that while clean-tech founders may have had ample experience developing technologies, many had little in building manufacturing capacity and operating businesses. That made it hard to compete in commodity fields with powerful incumbent players and ultra-thin margins.

The next boom

A lot has changed since then.

Clean technologies themselves have gotten better and cheaper. Renewables can now largely compete directly on cost with coal and natural-gas plants, following a massive buildout of manufacturing plants and solar and wind farms around the globe. Likewise, the improving price and performance of lithium-ion batteries is making electric vehicles more attractive to consumers and automakers.

“Despite the headwinds of the Trump administration, the march to clean energy and a clean economy is moving full speed ahead,” says Nancy Pfund, founder and managing partner at DBL Partners.

Meanwhile, Japan, the European Union, and China have all committed to effectively decarbonize their economies by around midcentury. Similarly, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and even fossil-fuel giants like BP, Shell, and Total have all announced “net zero” emissions plans.

Together, these trends have eliminated the technical risks from big parts of the clean-tech sector and set the stage for the development of major new markets. And little of this has been lost on investors.

From 2013 to 2019, early-stage investments in climate-related tech leaped from about $420 million to more than $16 billion, according to the PwC report. That’s three times the growth rate of venture investments into artificial intelligence, itself a booming market in recent years.

A number of venture capital firms dedicated to climate change have emerged during the last few years, including Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Congruent Ventures, Energy Impact Partners, G2VP, Greentown Labs, Lowercarbon Capital, and Powerhouse.

The field is also drawing heavy investment from generalist venture capital firms like Softback, Founders Fund, Sequoia Capital, Y Combinator, and the two firms most closely associated with the first clean-tech boom and bust, Kleiner Perkins and Khosla Ventures. Union Square Ventures is raising a dedicated climate fund of $100 to $200 million, the Wall Street Journal reported earlier this month.

And corporations themselves have launched their own funds, including Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund, Microsoft’s Climate Innovation Fund, and Unilever’s Climate & Nature Fund.

Emily Kirsch, founder and chief executive of Oakland-based Powerhouse, says that Biden’s arrival in the White House could immediately boost the market for electric cars, batteries, and charging infrastructure. During the campaign, the president-elect pledged to sign a series of “day one” executive orders, including ones that would raise fuel economy standards and steer hundreds of billions in annual government spending toward clean power and vehicles, she notes.

The administration’s goal of installing 500 million solar panels and 60,000 wind turbines within five years, in part by opening up federal lands for such developments, will also significantly expand the US market for renewables. And the plan to create a new Energy Department moonshot research program focused on climate, known as ARPA-C, could accelerate advances in green hydrogen, long-duration energy storage, and cleaner ways of producing steel, concrete, and chemicals, Kirsch says.

What has changed

But how different will things be this time around?

Varun Sivaram, a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and one of the authors of the MIT report, says there are several ways that investors can avoid the previous mistakes. They can invest at later stages, when the technological risk has been addressed; focus on digital and software opportunities that don’t require the buildout of massive factories or plants; adopt an investment model that doesn’t count on returns as rapidly; and look for technologies that slot into, rather than compete against, existing ways of manufacturing products.

All these things are happening to various degrees.

Bill Gates’s $1 billion Breakthrough Energy Ventures fund—which includes investments from two of the most prominent VCs of the last boom, John Doerr and Vinod Khosla—invests on 20-year cycles. Likewise, MIT’s “tough tech” incubator, The Engine, doesn’t count on earning its money back for 12 to 18 years.

The current investment cycle is also far more diversified.

While the first boom was primarily about cleaning up the power sector and early efforts to address transportation—and was particularly concentrated on thin-film solar, electric cars, and advanced biofuels—venture capital is now ranging more widely. VCs are funding protein-replacement companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods; startups developing cleaner ways of producing cement and steel, like CarbonCure Technologies and Boston Metal; businesses working on carbon removal and recycling, like Climeworks and Opus 12; companies supporting the creation of carbon offsets and markets, like Pachama, Indigo Ag, and Nori; and those offering ways to reduce the wildfire risks associated with climate change, such as Zonehaven, Buzz Solutions, and Overstory.

New boom, new risks

Every investor interviewed for this piece stressed that the technologies have matured, the market is now ripe for these companies, and the hard-won lessons from the last bust have been internalized.

But each new boom invariably creates excessive hype around certain sectors and players, and ultimately reveals deeper market pitfalls than were obvious at the start.

Some risks are already clear. The fragile economy could still take a deeper dive or require a long time to really recover, potentially limiting the availability of capital for major investments and projects. In addition, powerful incumbent fossil-fuel players will continue to battle hard to retain their market dominance, and plenty of groups and politicians will keep up the fight against ambitious climate policies.

And it would take a lot of costly supporting infrastructure to make some of these bets really pay off, like pipelines to transport captured carbon dioxide or a modernized grid to accommodate rising shares of renewable power.

Sivaram says that certain markets might already be getting a little frothy, including those for electric vehicles. Some of the investments going into carbon-removal and carbon-market startups have also raised eyebrows among close observers of those spaces.

The bigger risk, however, is still that promising technologies won’t get the early funding they need to develop into successful businesses, Sivaram adds.

With most VCs again avoiding long-term investments this time around and steering clearer from technical risks, increasingly generous public funding will be needed to ensure the breakthroughs that will drive costs down further and fill in some of the critical gaps in clean energy. Whether Biden can direct enough federal money to seed the marketplace with the next generation of startups could be one of the crucial factors determining how sustainable and long-lasting this boom will be.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

What’s coming next for fusion research

A year ago, scientists generated net energy with a fusion reactor. This is what’s happened since then.

Is this the most energy-efficient way to build homes?

Airtight and super-insulated, a passive house uses around 90% less energy.

The University of California has all but dropped carbon offsets—and thinks you should, too

It uncovered systemic problems with offset markets and recommended that the public university system focus on cutting its direct emissions instead.

Super-efficient solar cells: 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2024

Solar cells that combine traditional silicon with cutting-edge perovskites could push the efficiency of solar panels to new heights.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.