Geoengineering researchers have halted plans for a balloon launch in Sweden

An independent advisory committee recommended the team hold off on balloon equipment tests until it holds public discussions.

In an unexpected move, the advisory committee for a Harvard University geoengineering research project is recommending that the team suspend plans for its first balloon flight in Sweden this summer.

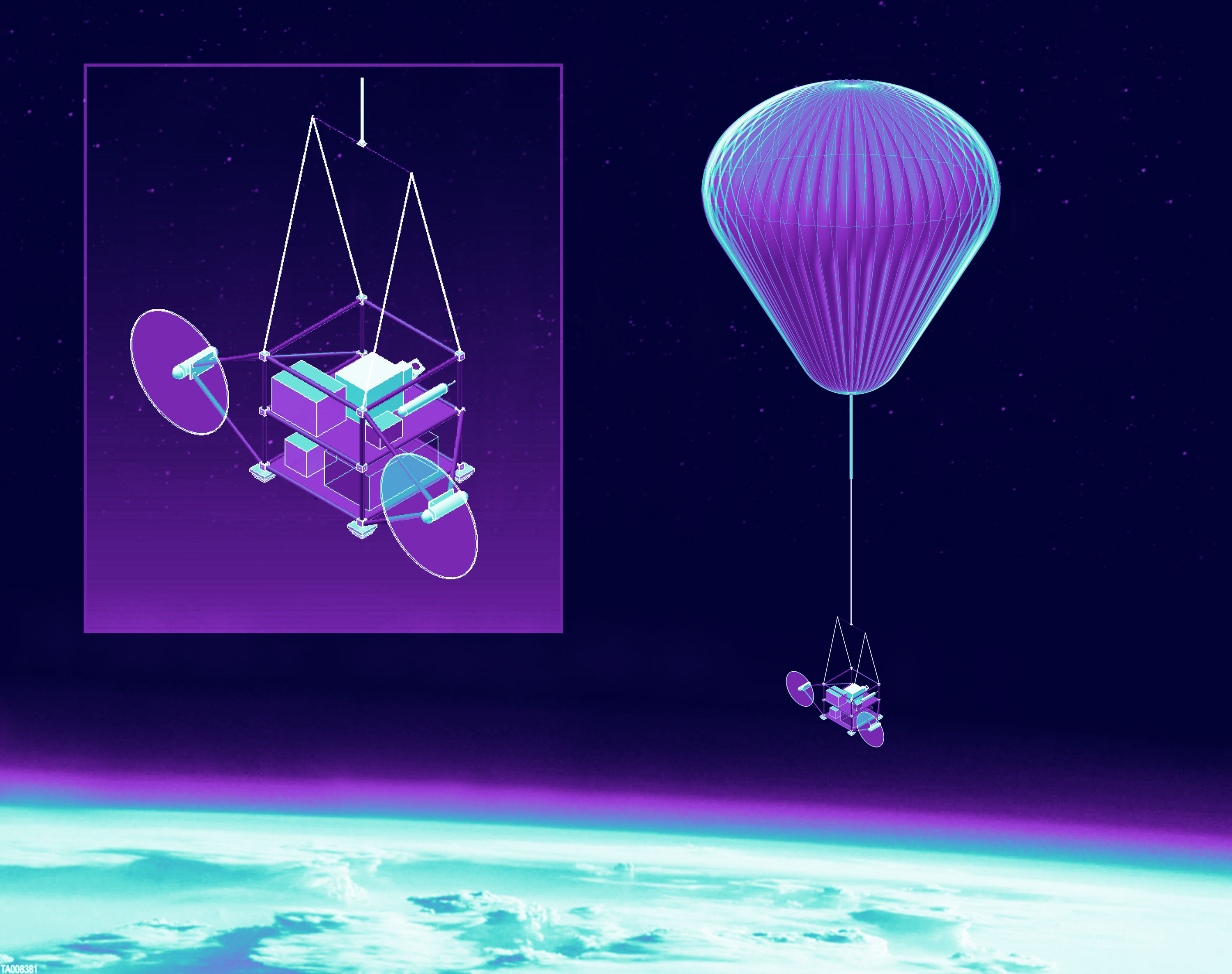

The purpose of that initial flight was to evaluate the propelled balloon's equipment and software in the stratosphere. In subsequent launches, the researchers hope to release small amounts of particles to better understand the risks and potential of solar geoengineering, the controversial concept of spraying sulfates, calcium carbonate or other compounds above the Earth to scatter sunlight and ease global warming. These would mark the first geoengineering-related experiments conducted in the stratosphere.

But the committee has determined that the researchers should hold off on even the preliminary equipment tests until they’ve held discussions with members of the public in Sweden. David Keith, a Harvard climate scientist and member of the research team, said they will abide by the recommendations.

The decision is likely to push the launch into 2022, further delaying a project initially slated to begin as early as 2018. It also opens up the possibility that the initial flights will occur elsewhere, as the researchers had selected the Esrange Space Center in Kiruna, Sweden in part because the Swedish Space Corporation could accommodate a launch this year.

Moreover, that company said in its own statement that it decided not to conduct the flights as well, following recent conversations with geoengineering experts, the advisory board and other stakeholders.

Harvard set up the advisory committee in 2019 to review the proposed experiments and ensure the researchers take appropriate steps to limit risks, seek outside input, and operate in a transparent manner.

In a statement, the committee said it has begun the process of working with public engagement specialists in Sweden and looking for organizations to host conversations.

“This engagement would help the committee understand Swedish and Indigenous perspectives and make an informed and responsive recommendation about the equipment test flights in Sweden,” the committee said. “The engagement in Sweden would also contribute to the committee’s deliberations regarding the proposed particle release flights and contribute to a growing body of research and practice about public governance of geoscience research.”

Frank Keutsch, principal investigator on the research project, said in a statement that the team: "fully supports the Advisory Committee's recommendation that any equipment test flights in Sweden need to be suspended until the committee can make a final recommendation about those flights based on robust public engagement in Sweden that is broadly inclusive of indigenous populations. Our research team intends to listen closely to this public engagement process to inform the experiment moving forward."

In recent weeks, several environmental groups and geoengineering critics have called on Swedish government officials and the heads of the Swedish Space Corporation to halt the project.

Solar geoengineering “is a technology with the potential for extreme consequences, and stands out as dangerous, unpredictable, and unmanageable,” read a letter issued by Greenpeace Sweden, Biofuelwatch, and other organizations. “There is no justification for testing and experimenting with technology that seems to be too dangerous to ever be used.”

The Saami Council, which promotes the rights and interests of the indigenous Saami people in Sweden and neighboring regions, also asked the committee and the Swedish Space Corporation to cancel the flights, stating they: "threaten the reputation and credibility of the climate leadership Sweden wants and must pursue as the only way to deal effectively with the climate crisis: powerful measures for a rapid and just transition to zero emission societies, 100% renewable energy and shutdown of the fossil fuel industry."

In February, I published a feature story exploring what the Harvard researchers hope to learn from the experiments.

“My view is actually very strongly that I seriously hope we’ll never get in a situation where this actually has to be done, because I still think this is a very scary concept and something will go wrong," Keutsch told me.

“But at the same time, I think better understanding what the risks may be is very important,” he added. “And I think for the direct research I’m most interested in, if there is a type of material that can significantly reduce [climate change] risks, I do think we should know about this.”

This story was updated to include the concerns expressed by the Saami Council.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

What’s coming next for fusion research

A year ago, scientists generated net energy with a fusion reactor. This is what’s happened since then.

Is this the most energy-efficient way to build homes?

Airtight and super-insulated, a passive house uses around 90% less energy.

The University of California has all but dropped carbon offsets—and thinks you should, too

It uncovered systemic problems with offset markets and recommended that the public university system focus on cutting its direct emissions instead.

Super-efficient solar cells: 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2024

Solar cells that combine traditional silicon with cutting-edge perovskites could push the efficiency of solar panels to new heights.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.