DeepMind says it will release the structure of every protein known to science

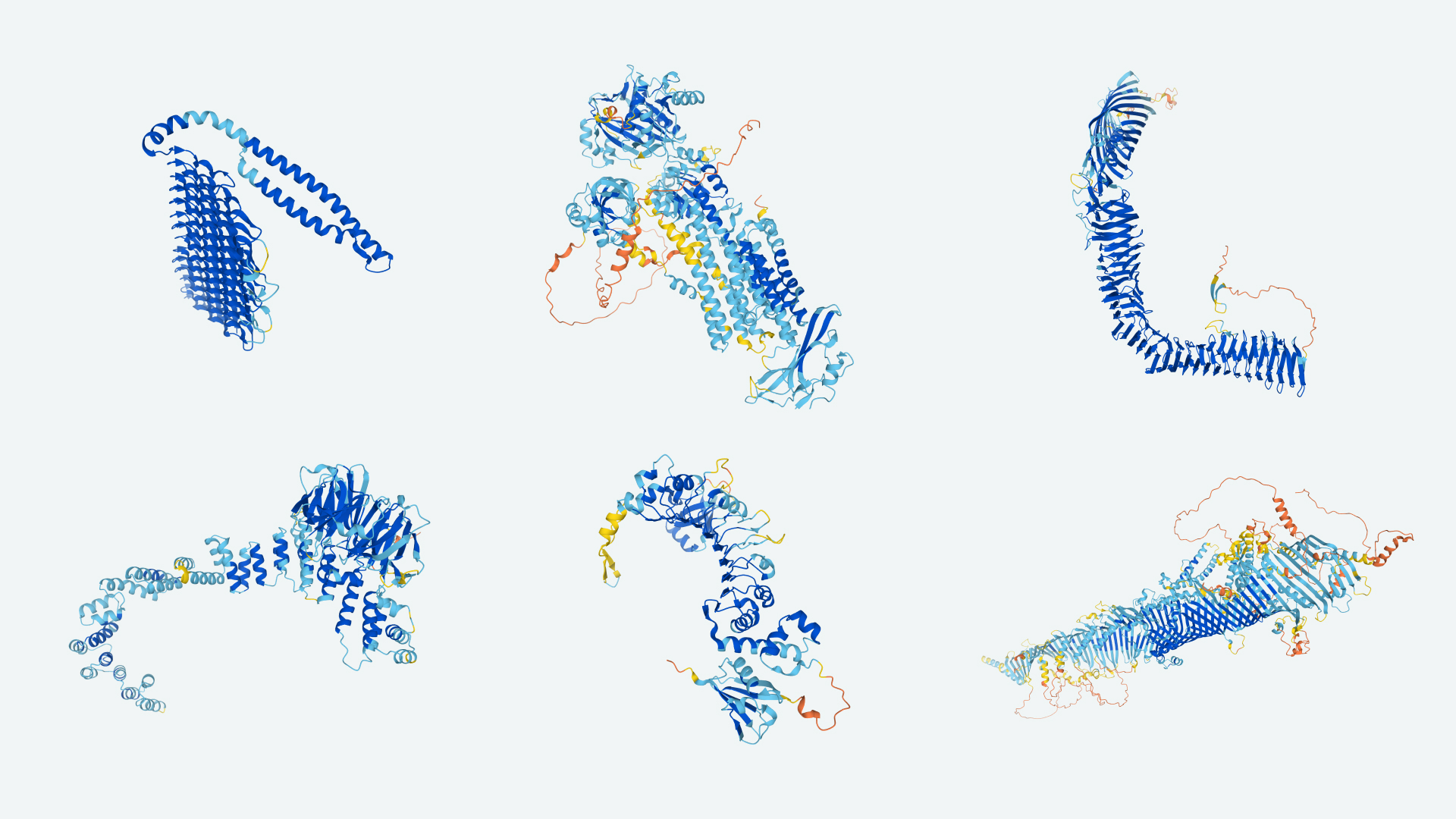

The company has already used its protein-folding AI, AlphaFold, to generate structures for the human proteome, as well as yeast, fruit flies, mice, and more.

Back in December 2020, DeepMind took the world of biology by surprise when it solved a 50-year grand challenge with AlphaFold, an AI tool that predicts the structure of proteins. Last week the London-based company published full details of that tool and released its source code.

Now the firm has announced that it has used its AI to predict the shapes of nearly every protein in the human body, as well as the shapes of hundreds of thousands of other proteins found in 20 of the most widely studied organisms, including yeast, fruit flies, and mice. The breakthrough could allow biologists from around the world to understand diseases better and develop new drugs.

So far the trove consists of 350,000 newly predicted protein structures. DeepMind says it will predict and release the structures for more than 100 million more in the next few months—more or less all proteins known to science.

This story is only available to subscribers.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

“Protein folding is a problem I’ve had my eye on for more than 20 years,” says DeepMind cofounder and CEO Demis Hassabis. “It’s been a huge project for us. I would say this is the biggest thing we’ve done so far. And it’s the most exciting in a way, because it should have the biggest impact in the world outside of AI.”

Proteins are made of long ribbons of amino acids, which twist themselves up into complicated knots. Knowing the shape of a protein’s knot can reveal what that protein does, which is crucial for understanding how diseases work and developing new drugs—or identifying organisms that can help tackle pollution and climate change. Figuring out a protein’s shape takes weeks or months in the lab. AlphaFold can predict shapes to the nearest atom in a day or two.

The new database should make life even easier for biologists. AlphaFold might be available for researchers to use, but not everyone will want to run the software themselves. “It’s much easier to go and grab a structure from the database than it is running it on your own computer,” says David Baker of the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington, whose lab has built its own tool for predicting protein structure, called RoseTTAFold, based on AlphaFold’s approach.

In the last few months Baker’s team has been working with biologists who were previously stuck trying to figure out the shape of proteins they were studying. “There’s a lot of pretty cool biological research that’s been really sped up,” he says. A public database containing hundreds of thousands of ready-made protein shapes should be an even bigger accelerator.

“It looks astonishingly impressive,” says Tom Ellis, a synthetic biologist at Imperial College London studying the yeast genome, who is excited to try the database. But he cautions that most of the predicted shapes have not yet been verified in the lab.

Atomic precision

In the new version of AlphaFold, predictions come with a confidence score that the tool uses to flag how close it thinks each predicted shape is to the real thing. Using this measure, DeepMind found that AlphaFold predicted shapes for 36% of human proteins with an accuracy that is correct down to the level of individual atoms. This is good enough for drug development, says Hassabis.

Previously, after decades of work, only 17% of the proteins in the human body have had their structures identified in the lab. If AlphaFold’s predictions are as accurate as DeepMind says, the tool has more than doubled this number in just a few weeks.

Even predictions that are not fully accurate at the atomic level are still useful. For more than half of the proteins in the human body, AlphaFold has predicted a shape that should be good enough for researchers to figure out the protein’s function. The rest of AlphaFold’s current predictions are either incorrect, or involve the third of proteins in the human body that don’t have a structure at all until they bind to others. “They’re floppy,” says Hassabis.

“The fact that it can be applied at this level of quality is an impressive thing,” says Mohammed AlQuraish, a computational biologist at Columbia University who has developed his own software for predicting protein structure. He also points out that having structures for most of the proteins in an organism will make it possible to study how these proteins work as a system, not just in isolation. “That’s what I think is most exciting,” he says.

DeepMind is releasing its tools and predictions for free and will not say if it has plans for making money from them in future. It is not ruling out the possibility, however. To set up and run the database, DeepMind is partnering with the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, an international research institution that already hosts a large database of protein information.

For now, AlQuraishi can’t wait to see what researchers do with the new data. “It’s pretty spectacular,” he says “I don’t think any of us thought we would be here this quickly. It’s mind boggling.”