Here’s what a lab-grown burger tastes like

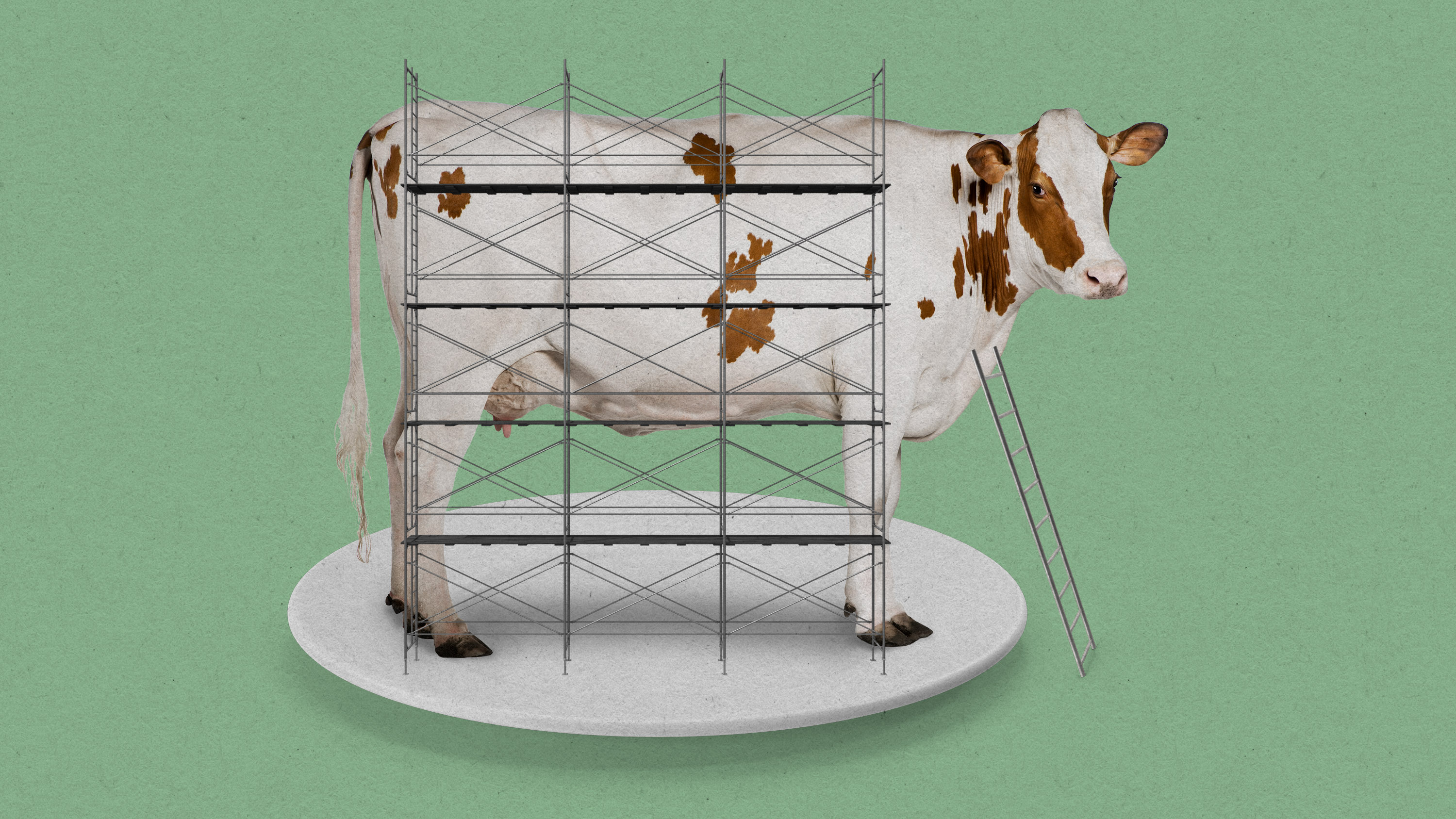

Companies are engineering meat in the lab. Will anyone eat it?

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review's weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.

Sitting in a booth in a hotel lobby in Brooklyn, I stared down the lineup of sliders, each on a separate bamboo plate. On the far left was a plant-based burger from Impossible Foods. On the right, an old-fashioned beef burger. And in the middle, the star of the show: a burger made with lab-grown meat.

I’m not a vegan or even a vegetarian. I drink whole milk in my lattes, and I can’t turn down a hot dog at a summer cookout. But as a climate reporter, I’m keenly aware of the impact that eating meat has on the planet. Animal agriculture makes up nearly 15% of global greenhouse-gas emissions, and beef is a particular offender, with more emissions per gram than basically any other meat.

So I’m really intrigued by the promise that cultivated meat could replicate the experience of eating meat without all that climate baggage. I had high hopes for my taste test. Could a lab-grown burger be everything I dreamed it might be?

The competition

“We’re food-safe in this house,” said Jess Krieger, founder and CEO of the cultivated-meat company Ohayo Valley, as she pulled on a pair of black plastic gloves to lay out the three burgers I was about to try. My tasting would culminate in a sample of her company’s lab-grown Wagyu burger.

We started with a plant-based burger from Impossible Foods. Founded in 2011, the company makes meat alternatives from plants. The special ingredient is heme protein, which is cranked out by genetically engineered microbes and sprinkled in for that meaty flavor. I took a small bite of the Impossible burger, and if you ask me, the taste was a pretty good approximation of the real thing, though the texture was a bit looser and softer than beef. (If you’re based in the US, you may have tried this one already yourself. In Europe, heme still hasn’t been approved by regulators, so Impossible’s products don’t include it there.)

Next on the docket was the beef burger. By the way, none of these sliders had any sort of sauces or toppings on them, and Krieger says they were seasoned identically, for a fair comparison. I truly have nothing to say about this one—it was just a plain burger. Even as I was chewing, I had my eyes on the final item on my tasting menu for the day: the lab-grown version.

The future of meat?

Ohayo Valley’s Wagyu burgers start out as a small biopsy of muscle taken from a young cow. Cells from that sample, mostly muscle cells and fibroblasts (which can transform into fat cells as a cow grows), can then be cultivated in the lab, growing and dividing over and over again. Having a mix of muscle cells, fibroblasts, and mature fat cells in the final product is key for the flavor, Krieger says.

Once the cells have proliferated enough, they’re washed with salt water to clear out the broth they’re grown in and stored in the fridge overnight. Then they can go into a burger as soon as the next day. Most of Ohayo’s work is still happening at a small lab scale, Krieger said, so altogether it took about three weeks to grow all the cells for my slider, along with four others the team planned to serve at an event later that day.

The burger on my plate was actually only about 20% lab-grown material, Krieger explained. The company’s plan is to blend its cells with a base of plant-based meat (she wouldn’t tell me much about this base, just that it’s not Ohayo’s recipe). Plants can help provide the structure for alternative meats, Krieger says. One other major benefit to this blending technique is financial: the lab-grown components are expensive, so mixing in plants can help keep costs down. My colleague Niall Firth wrote about this process of blending lab-grown and plant-based meat (and Ohayo Valley) in 2020.

The world’s first lab-grown burger, served at a conference in 2013, cost an estimated $330,000 to make. The field has come a long way since, with Singapore becoming the first country to allow commercial sales of lab-grown meat in 2020. And in November 2022, a company in the US passed one of the final hurdles from the Food and Drug Administration.

All this context was swirling in my head as I picked up the lab-grown burger and took a bite.

It was definitely different from beef, but maybe not in a bad way. To me, the lab-grown burger had a strong resemblance to the one from Impossible Foods. The texture was similar, which makes sense since it was mostly made from plants.

Taste-wise, I thought the lab-grown meat may have been a bit closer to the beef burger, but I found myself wondering if I’d feel the same way if I didn’t know which was which. Was my brain tricking me into thinking it tasted more like meat, since I knew that there were animal cells in it? I took bites of all three burgers again to try to figure it out. I’m still not sure.

There are a lot of unanswered questions about lab-grown meat, including whether companies will be able to produce it at commercial scale, how expensive it’ll turn out to be, what the climate impacts will actually look like, and whether anyone will eat this in the first place.

Overall, we could probably use more options that are better for the climate than beef is today. I know that beans and tofu and lentils exist, and I’ve got some great vegetarian recipes I turn to sometimes. But I’m just not ready to give up burgers altogether. And I’m not alone—the vast majority of the world’s population still eats meat.

As the pressure of climate change ratchets up, more people are looking for compromises: alternatives that can replicate, or at least approximate, the experience of eating meat. I’m interested to see whether lab-grown meat can do anything to sway us from the old-fashioned version.

Related reading

- Impossible Foods is apparently working on making a plant-based filet mignon.

- My colleague Jess Hamzelou, who covers biotech, expressed some doubts about lab-grown meat in a newsletter last year.

- Cow-free burgers were on our list of 10 Breakthrough Technologies in 2019. For the occasion, our very own Niall Firth dove into the race to make a lab-grown steak.

Another thing

People are getting really creative when it comes to making jet fuel. While the stuff that powers our planes today is mostly fossil fuels, there are increasingly other options on the table, made of everything from used cooking oil to carbon dioxide sucked out of the atmosphere.

I’ve become obsessed with these new fuels, sometimes called sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs). What I’ve learned is that the details really matter: some could be a great solution for cutting emissions from aviation. Others could turn out to be a climate nightmare. Check out my story for more.

Keeping up with climate

Finally, states in the western US have reached an agreement to keep the Colorado River from going dry. The deal calls for the US federal government to dole out about $1.2 billion to groups with water rights if they temporarily cut use. (New York Times)

This story about one reporter’s quest to find a sustainable cat litter bag is hilarious and disheartening in equal parts. My takeaways? Plastics are tricky (to say the least), and individual actions can only do so much when it comes to climate change. (Heatmap News)

I loved these visualizations that show just how dominant China is in every stage of making batteries, from mining to refining to manufacturing. (New York Times)

→ EV batteries have become a huge point of political tension between China and the US. (MIT Technology Review)

Some people think Dolly Parton’s newest song is a climate anthem. For the record, Parton is a national treasure in my eyes, but she does have a history of tapping into the zeitgeist without really taking sides. (Grist)

This is a solid explanation on CATL’s new “semi-solid state” battery (the pun is all mine, I’m sorry). These new cells have double the energy density of most lithium-ion batteries on the market today and could hit large-scale production this year. (Inside Climate News)

Carbon removal startup Charm Industrial just got $53 million to remove 112,000 tons of carbon from the atmosphere by 2030. The deal with Frontier, a coalition backed by tech companies, is one of the largest in the space to date. (Bloomberg)

→ For more on how Charm’s bio-oil can store carbon and what questions remain, check out my colleague James Temple’s story from last year. (MIT Technology Review)

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

What’s coming next for fusion research

A year ago, scientists generated net energy with a fusion reactor. This is what’s happened since then.

Is this the most energy-efficient way to build homes?

Airtight and super-insulated, a passive house uses around 90% less energy.

The University of California has all but dropped carbon offsets—and thinks you should, too

It uncovered systemic problems with offset markets and recommended that the public university system focus on cutting its direct emissions instead.

Super-efficient solar cells: 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2024

Solar cells that combine traditional silicon with cutting-edge perovskites could push the efficiency of solar panels to new heights.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.