How Charm Industrial hopes to use crops to cut steel emissions

The startup believes its bio-oil, once converted into syngas, could help clean up the dirtiest industrial sector.

Charm Industrial has gained attention for its unusual approach to storing away carbon dioxide: converting plant matter into bio-oil that it then pumps into deep wells and salt caverns. (See related story.)

But the San Francisco startup is now exploring whether that oil could be used to cut emissions from iron and steelmaking as well, pursuing a new technical path for cleaning up the dirtiest industrial sector.

The iron and steel industry produces about 4 billion tons of carbon emissions each year, accounting for around 10% of all energy-related climate pollution, according to a 2020 report by the International Energy Agency. Those figures have risen sharply this century, driven by rapid economic growth in China and elsewhere.

The hefty emissions and increasingly strict climate policies in some areas, including Canada and the European Union, have started to compel some companies to explore cleaner ways of producing these essential building blocks of the modern world.

The Swedish joint venture Hybrit delivered the first commercial batch of green steel to Volvo last year. This partnership between the steel giant SSAB, the state-owned power company Vattenfall, and the mining company LKAB, used a manufacturing method that relied on carbon-free hydrogen in lieu of coal and coke. Other companies are exploring the use of facilities with equipment that captures carbon dioxide or, like Boston Metal, implementing entirely different electrochemical methods.

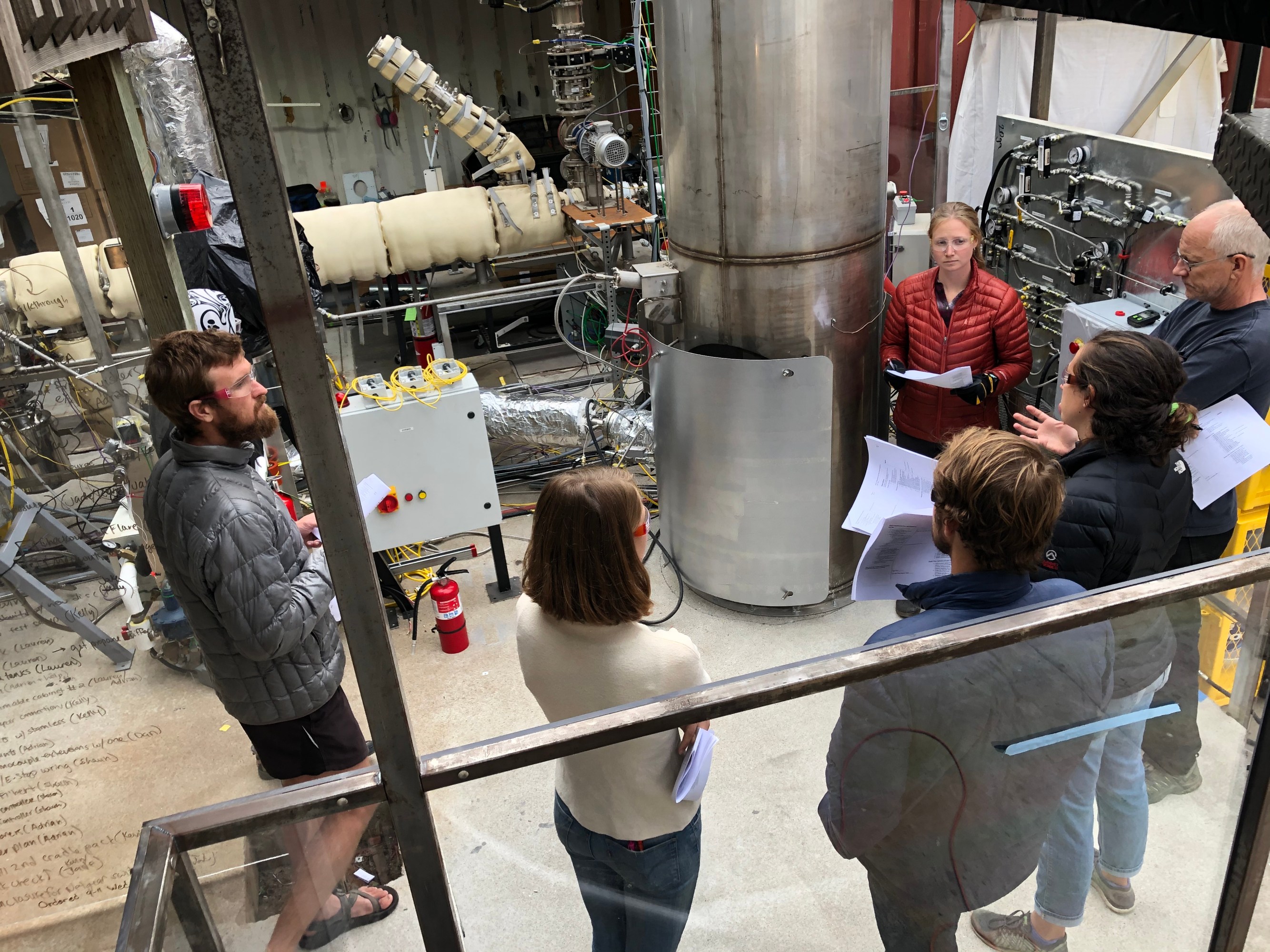

Charm is evaluating still another approach. In the back corner of the company’s warehouse, employees have been using a narrow metal contraption, known as a reformer, to react the company’s bio-oil with hot steam and oxygen. That produces what’s known as syngas, which is mostly a mix of carbon monoxide and hydrogen.

That could potentially be swapped into one method of producing iron and steel.

The most common form of steel production starts with a blast furnace, which heats iron ore, limestone, and coke, a form of coal, to temperatures above 1,500 ˚C. The resulting carbon-laden metal, known as “pig iron,” then moves into a second furnace, where oxygen is blown into it, impurities are removed, and other materials are added to produce various grades of steel.

Emissions occur at every stage of this process, including the extraction and production of iron, coal, and coke; the combustion of fuels to run the furnaces; and the chemical reactions that occur within them.

But about 7% of non-recycled steel today is produced in a different type of furnace, using what’s known as a direct-reduction method. It usually relies on natural gas to strip oxygen atoms off the iron oxide ore in a shaft furnace. This produces what’s known as sponge iron, which basically just needs to be melted and mixed with other materials. That second step can be done in what’s known as an electric arc furnace, which can run on carbon-free power from solar, wind, geothermal, or nuclear plants.

The method already produces fewer emissions than the blast furnace approach. But it can be made cleaner still by replacing the natural gas with alternatives, including carbon-free hydrogen in Hybrit’s case or syngas produced from crop remains in Charm’s.

Because those crops sucked the carbon that goes into the syngas out of the air, the process shouldn’t emit any more than it removes, CEO Peter Reinhardt says. If it were done in a facility with added equipment to capture emissions, it could even produce a form of negative-emissions steel, removing more than it releases, he says.

Reinhardt says the company is in discussion with several steelmakers about carrying out demonstration projects, exploring how it could deploy bio-oil-based syngas as a cleaner way of producing iron.

Charm is considering several market approaches, including selling syngas directly to steel manufacturers or producing its own hot briquetted iron, a product one step beyond sponge iron. Any company with an electric arc furnace could use that to produce steel. Most steel in the US is produced from recycled materials using such furnaces.

Charm, however, will face some obvious challenges.

First, the steel industry has decades of experience with existing manufacturing methods and has sunk massive amounts of capital into them.

“The blast furnace is one of the most energy-efficient machines that has ever been invented,” says Rebecca Dell, director of the industry program at ClimateWorks. “We’ve spent well over a century optimizing its performance. So people aren’t going to change without a real good reason.”

That reason will almost certainly need to include strict public policy mandates or incentives in more nations, particularly the US, China, India, and other fast-growing economies, as well as demand from customers looking to operate in greener ways.

Another question is how much this approach will do to address emissions. There has been a long history of companies claiming that bioenergy sources would produce more climate-friendly products than turned out to be true once the entire process was carefully scrutinized. Corn-based ethanol is a famous case.

“We’ve had some very bad experiences with bioenergy sources … and we need to learn the lessons from those,” Dell says. “So that’s a claim that needs to be interrogated. Even if it might be low carbon, it’s almost never carbon neutral.”

It’s also not clear if Charm’s approach will prove to be the most affordable or attractive way of cutting emissions from steel, given the other efforts underway.

But as Dell notes, iron and steel pollution is such a big and urgent problem that we’re likely to need a variety of solutions and should be spreading out our technological bets.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

What’s coming next for fusion research

A year ago, scientists generated net energy with a fusion reactor. This is what’s happened since then.

Is this the most energy-efficient way to build homes?

Airtight and super-insulated, a passive house uses around 90% less energy.

The University of California has all but dropped carbon offsets—and thinks you should, too

It uncovered systemic problems with offset markets and recommended that the public university system focus on cutting its direct emissions instead.

Super-efficient solar cells: 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2024

Solar cells that combine traditional silicon with cutting-edge perovskites could push the efficiency of solar panels to new heights.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.