When the race for fusion ground to a halt

A billion-dollar nuclear fusion machine was shuttered the day it was dedicated. It was never turned on.

On Friday, February 21, 1986, a group of 300 scientists and engineers gathered for a dedication ceremony at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL). After final tests, the completion of Mirror Fusion Test Facility-B (MFTF-B) was celebrated, and a letter from John Herrington, Ronald Reagan’s secretary of energy, was presented to program director T. Kenneth Fowler, extending his congratulations on a job well done.

On the very same day, after nearly a decade of development and close to a billion dollars of funding (in 2023 dollars, that is), the project was shut down, the massive machine never having been turned on.

“I want all of you to know how much I regret the fact that, just as you complete this remarkable new facility, the budget pressures dictate that we must put it into standby and not operate it as you might have hoped,” wrote Herrington in the letter to Fowler. “This is frustrating, and perhaps not the best use of our national talent and resources, but we must bring the deficit under control.”

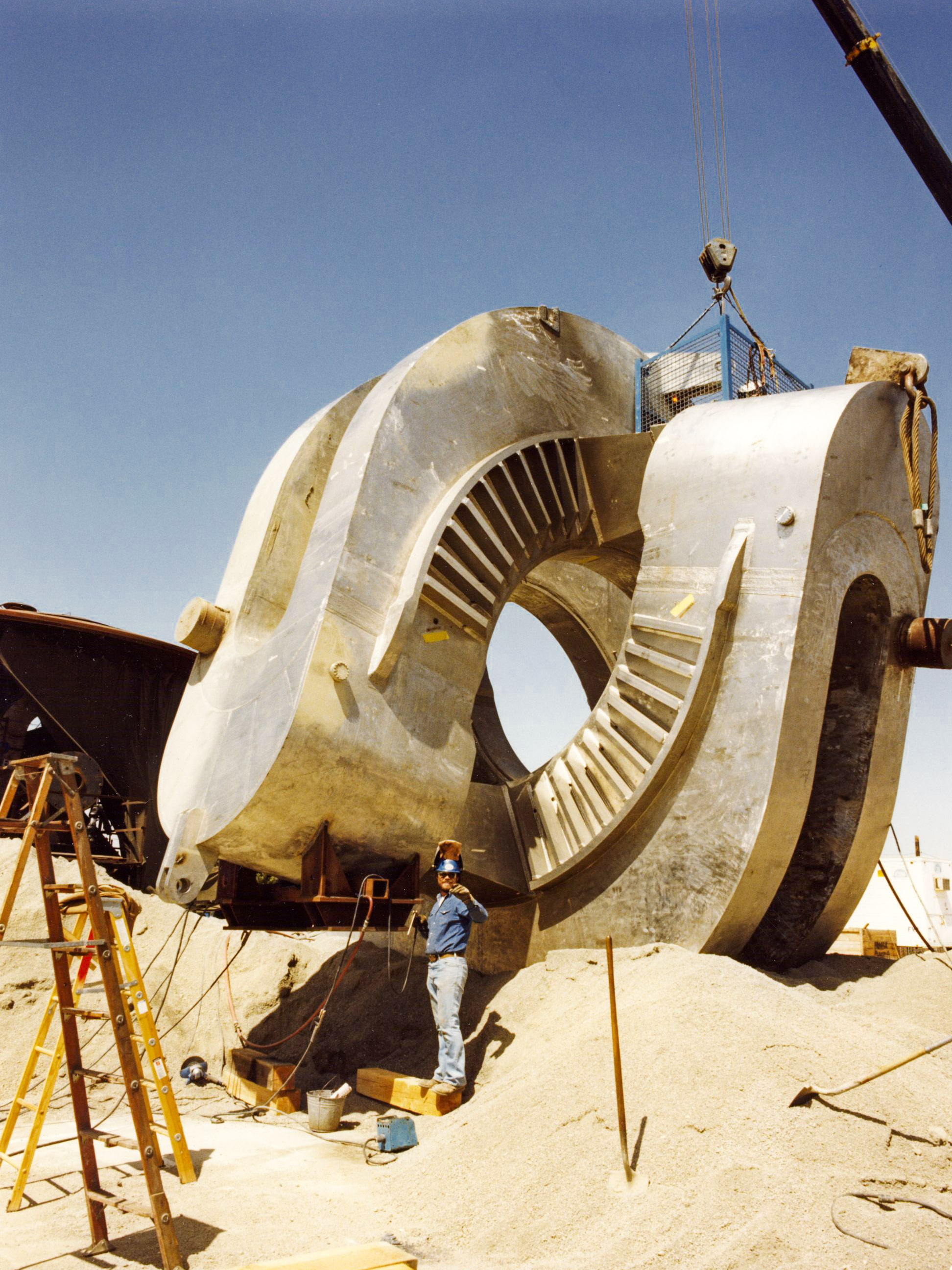

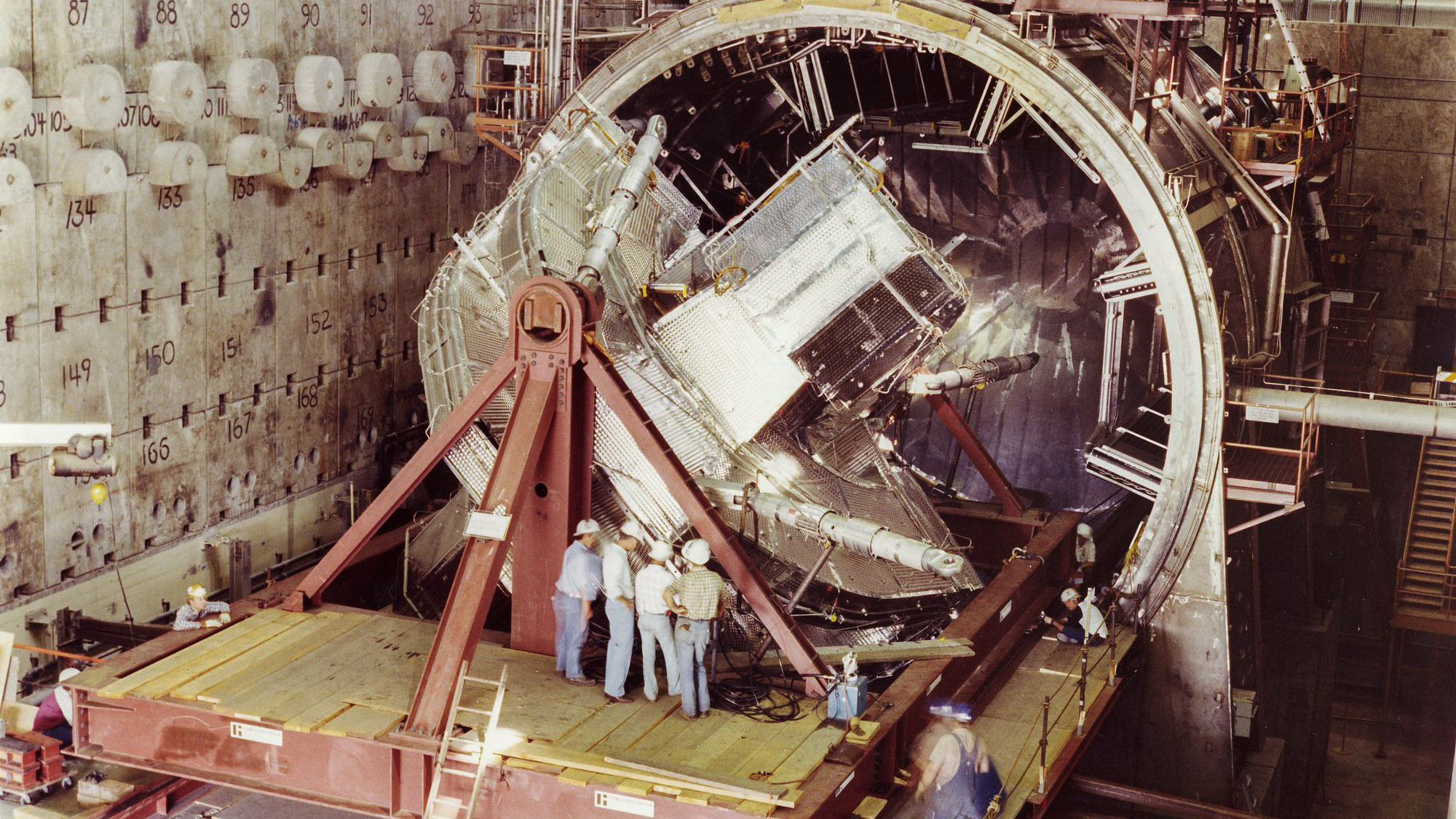

I came across photos from the construction of the facility’s components on LLNL’s website and was captivated by one from 1980 showing a strange twisting mass of metal that at the time was the largest superconducting magnet in the world.

This 350-ton magnet was encased in stainless steel built in a distinctive “yin-yang” shape; its interior was cooled by pumping liquid helium through the vessel. Thirty miles of wire were wound over the course of a year to make the magnet’s conductor.

The construction was capable of generating magnetic fields 150,000 times stronger than Earth’s.

The energy crisis of the 1970s had motivated the US to throw lots of money at alternative energy sources, and two major research pathways emerged in the quest for nuclear fusion power: the doughnut-shaped tokamak design used by researchers at Princeton and MFTF-B’s approach, which involved bouncing superheated plasma off two opposing “magnetic mirrors” at either end of a linear vessel.

MFTF-B program director Fowler was quoted as saying, “Building big machines is a mixture of lead times, resources, prudence, and gambling.” But the gamble didn’t pay off.

The Reagan administration’s decision to mothball the machine came as a gut punch to the researchers. And Livermore’s Building 431, the project’s home, was demolished in 2005 after failing to meet the threshold of historical significance to be protected on the National Register of Historic Places.

With the recent news that LLNL’s National Ignition Facility had achieved the first nuclear fusion reaction to produce a net energy gain, the outlook for fusion research looks brighter again.

The key to success turned out to be containing the plasma within 192 high-powered lasers, focused on a tiny pellet. Pounding it with 2 million joules of energy created a fusion reaction that lasted for 100 trillionths of a second.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

What’s coming next for fusion research

A year ago, scientists generated net energy with a fusion reactor. This is what’s happened since then.

Is this the most energy-efficient way to build homes?

Airtight and super-insulated, a passive house uses around 90% less energy.

The University of California has all but dropped carbon offsets—and thinks you should, too

It uncovered systemic problems with offset markets and recommended that the public university system focus on cutting its direct emissions instead.

Super-efficient solar cells: 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2024

Solar cells that combine traditional silicon with cutting-edge perovskites could push the efficiency of solar panels to new heights.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.